It had to be a girls’ school, whites only! This was South Africa in 1972 when apartheid was at its fiercest. I had reasonable English qualifications – a 2.1 degree from the University of North Wales in History and English and a year’s training diploma. I felt armed to teach the world! Johannesburg was another world. Nobody could help me begin as I was viewed as a foreigner. There was no TES or online services like Teacher Horizons so where to apply seemed a mystery.

It was only at a party when I mentioned my dilemma that I was told to go direct to the Ministry of Education in Pretoria. Several months of heavy paper-work followed as everything had to be delivered by hand. Cafes did not seem to exist in 70’s Pretoria so we always had took flask to drink coffee on the steps of the ominously looming Voortrekker monument.

Six months later – all the qualifications accepted – I was offered a post at Johannesburg High School for Girls in Hillbrow. I had not passed my driving test so it would be an hour’s journey on two buses. I was really scared of waiting in the wrong queue for the wrong bus, but this would be impossible.

Large signs declared ‘Whites Only’ or ‘Blacks, Bantu, Coloured Only’ so there could be no mistake. ‘Whites Only’ queues had only 2 or 3 people waiting whilst the “others” were packed with an ill-sorted crowd of women wearing woolly berets with babies on their backs and men in ill-fitting jackets or uniforms ready for their menial jobs. I could not possibly be in the wrong place – even the park benches had white painted signs on them in large print ‘ SLEGS VIR BLANKES’.

Large signs declared ‘Whites Only’ or ‘Blacks, Bantu, Coloured Only’ so there could be no mistake. ‘Whites Only’ queues had only 2 or 3 people waiting whilst the “others” were packed with an ill-sorted crowd of women wearing woolly berets with babies on their backs and men in ill-fitting jackets or uniforms ready for their menial jobs. I could not possibly be in the wrong place – even the park benches had white painted signs on them in large print ‘ SLEGS VIR BLANKES’.

School began at 8am with Assembly. Teachers had to be there on the stage in full view. The girls wore a white tunic dress, black blazer with pink binding and black lace-up shoes. Variations did not occur. They were extremely polite and formal. I was teaching History and English. History lessons became increasingly difficult as the rest of the world’s history was of no interest – only South African history was on the curriculum. This emphasised the importance of the Great Trek of 1835 when Dutch Protestant settlers forced their way into the interior of the Southern Africa ruthlessly crushing the tribes such as the Xhosa, Zulus and Ndebele who stood in their way. A white South African teacher had to present an entirely biased account of this event as described in great detail in the text books. No other material was allowed in class. In fact this very biased approach to History led to my teaching more English which could be better manipulated to broaden the minds of my pupils.

In my two years teaching there I grew to like the girls. They were in awe of my mini-skirts and varying coloured nail varnish – a product of the swinging sixties! There were no discipline problems as they were too regimented to rebel. They had no lunch-breaks -only short breaks before going home at 2pm so they did not socialise much in school-time. My favourite lessons were my English library lessons where I collected a small amount of Rand from each pupil and they took it in turns to buy a book of their choice. Every month we had an informal chat in groups about the books they had been reading and this did seem to break down some of the rigidity of pupils sitting in rows of desks putting their hands up to ask a question. I even managed to sneak in the odd poem by a black South African author which I was trying to collect and hope to make them realise that life was not just “whites only.”

One of the great advantages of school finishing early was that my husband working shifts could sometimes collect me on a Friday and we could drive to freedom – Swaziland, Mozambique or Lesotho to see the beautiful mountain scenery of the Drakensburg, eat fresh prawns by the sea in Lourenco Marques and relax amongst the colourful tribespeople over the border.

One of the great advantages of school finishing early was that my husband working shifts could sometimes collect me on a Friday and we could drive to freedom – Swaziland, Mozambique or Lesotho to see the beautiful mountain scenery of the Drakensburg, eat fresh prawns by the sea in Lourenco Marques and relax amongst the colourful tribespeople over the border.

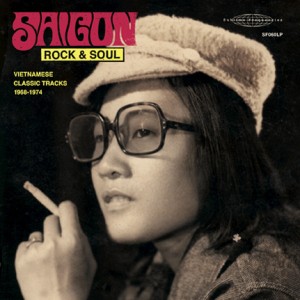

What a surprise to be told we were being transferred to Saigon. When informed my reply was “I’ve always wanted to go to China!” showing my lack of geographical and historical knowledge. Especially as Vietnam was THE story of the sixties, being torn between the North and the South – the Americans losing troops disastrously trying to hold back the Communist tide. However we were being sent there as a couple because the general feeling was that the Americans were successfully handing over the reins to the South Vietnamese. This was 1974.

I tried to improve my French at the Alliance Francaise as learning Vietnamese seemed too daunting. There I met Madame Pho from the Buddhist University who gave me an introduction for an interview to teach English. They could pay my taxi fare but no salary. The taxi each way would be less than £1.

I was to teach or lecture on ‘The History of English Literature’ and on a Friday afternoon, conversational English. My arrival caused a stir as I was ‘the real thing” – a genuine English accent rather than American twang. When I walked into the classroom I entered a fancy-dress parade – soldiers in khaki, naval uniforms, teenagers in fashionable jeans and American slogan T shirts, girls in traditional ao-dai, long silk tunics with slits to the waist above black silk pyjama-like trousers. They all lined up their shoes and sandals to enter the classroom. The only teaching aid was white chalk – the only visual aid “myself”.

I was to teach or lecture on ‘The History of English Literature’ and on a Friday afternoon, conversational English. My arrival caused a stir as I was ‘the real thing” – a genuine English accent rather than American twang. When I walked into the classroom I entered a fancy-dress parade – soldiers in khaki, naval uniforms, teenagers in fashionable jeans and American slogan T shirts, girls in traditional ao-dai, long silk tunics with slits to the waist above black silk pyjama-like trousers. They all lined up their shoes and sandals to enter the classroom. The only teaching aid was white chalk – the only visual aid “myself”.

The students took copious notes and their English seemed reasonable until we came upon titles such as D.H.Lawrence’s “The Rainbow” – no use explaining subtleties of relationships. I had to draw on the board what was a rainbow without coloured chalk of course.

The conversation classes proved quite challenging as 70 students crammed into a small classroom only kept bearable from the afternoon heat by one whirring overhead fan. I was given a list of topics to discuss and tried to divide the class into groups although 10 in a group is far too many. One topic “Holidays” was a failure – nobody had spare dollars, visas were required to leave the country, some were waiting to be called up for military service. If they could only get to France they would escape the nightmare of war on their own doorstep. They were not planning a holiday – they would not return!

I tended to wear long skirts in keeping with Buddhist codes of decency. Leaving the blue and yellow taxi with no air conditioning I gingerly stepped into the alley leading to our flat, lifting my skirts to avoid the splashes of urine, squashed fruit and vegetables, even rats running out of the wooden crates where some families huddled at night. There was a midnight curfew when the streets suddenly became eerily quiet and you stayed put behind barred doors at your peril.

Mid-April 1975. Little did we know Saigon had been infiltrated by a large army of communist supporters – North and South Vietnamese look exactly the same, only with different opinions – many were digging in along tunnels leading almost to the centre of Saigon. The streets became much quieter – fewer bikes, cycles, taxis, mopeds and cars, I did not know it was my last visit to the Buddhist University and I never said goodbye. I hope not too many of my students were killed when the North Vietnamese swarmed into the city.

I myself was airlifted by the New Zealand Air Force to Singapore. I grabbed my tennis racquet and sewing machine (always regretted not taking my photo albums) before piling in with the other evacuees boarding the Bristol freighter. My husband left by helicopter two weeks later when Saigon was taken over by the North Vietnamese.

Our next posting sounded like heaven, “Utopia.” It was in fact Ethiopia! This was in 1976 when Colonel Mengistu was ruthlessly enforcing his “ongoing revolution.” Foreigners were not very welcome, basic foods were in short supply and there was a midnight curfew.

Our next posting sounded like heaven, “Utopia.” It was in fact Ethiopia! This was in 1976 when Colonel Mengistu was ruthlessly enforcing his “ongoing revolution.” Foreigners were not very welcome, basic foods were in short supply and there was a midnight curfew.

Again through word of mouth I was offered a job teaching English at General Wingate Secondary School. I plucked up courage to enter a small dingy classroom crammed with over eighty pupils not knowing a word of English. I noticed the girls’ intricately braided hairstyles, the holey sweaters and complete lack of writing materials, and admitted defeat. I was saved by the British Council offering me a job as Educational Assistant in charge of administrating the G.C.E. exams still being held at two or three schools, the occasional local pupil gaining a scholarship to England, and best of all organising a Shakespeare production or art exhibition. Only I had tickets so was much sought after in the culture-starved capital of Addis Ababa.

Sadly these were curtailed one by one as being examples of “Western decadence” and not furthering “the great cause.” It was several months later the three Western journalists remaining in Addis (including my husband) were given 48 hours to leave the country. I moved to a friend’s house for safety’s sake, packed up our “used household effects”, said goodbye to a reduced British Council staff and took the flight to Nairobi just before the airport closed.