When Susanna Harper engaged her grade eight and nine students in oral history projects, parents would often tell her, ‘We don’t have any history in our family.’ It was these families—who claimed to have no interesting history in their family—who often discovered the most compelling stories.

“You have the students that think there’s nothing interesting in their family history at all and I have to convince them a bit. That’s the really challenging part. And the most challenging is, of course, when the parents then also believe that. I’ve had parents email me and say there’s nothing interesting in our family,” Harper tells Teacher Horizons, of her work teaching history in South Africa and Uzbekistan.

“I usually tell them I don’t believe them because every family has stories. They just don’t believe that they are valuable.”

In international school communities, families from all over the world converge and consequentially, “There are so many stories to record.” For humanity educators, Teacher Horizons can help connect teachers to learning environments that celebrate unique teaching practices.

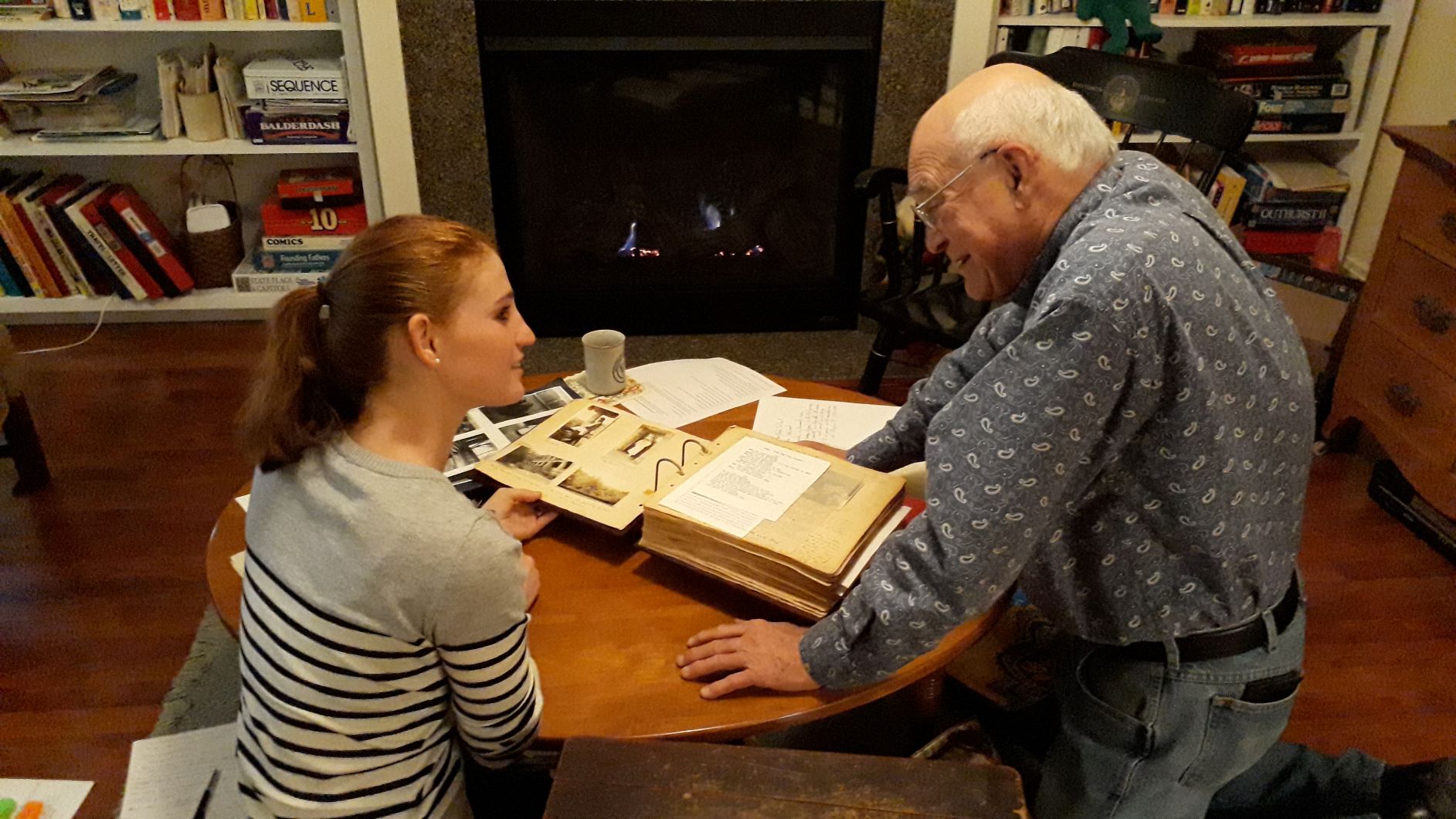

When students become oral history practitioners, they find themselves—perhaps for the first time—really listening to other people’s stories.

Susanna Harper

Incorporating oral history and virtual visits into the humanities

Oral history is a research methodology in which information is collected from individuals via audio/video recordings or transcripts. This process enables historians to preserve different perspectives about a particular event for future generations.

Harper encourages her young historians to engage in the practice, with students carrying out and recording interviews with several family members to learn about a particular event that had a major impact on their family. She further incorporates these primary sources into her teaching by inviting individuals into the classroom (virtually as of late) to share their lived experiences with the students.

When Harper invited Veronica Philipps, a Holocaust survivor, to speak via webinar with her class, students relayed their surprise over the profound impact her story made on them. “Even though Mrs. Phillips spoke to us virtually, I felt her presence, along with her emotions,” one student wrote to Harper.

Educators understand the significance these visits have on students. “The shared experience of listening to a survivor bearing witness is like no other experience….It inevitably affects us deeply and…changes the way we feel about history and ourselves,” writes Margot Stern Strom, the founder and executive director of Facing History and Ourselves, an organization which provides resources for teachers.

Telling a more complete story than the textbook

Harper explains the value of collecting oral histories comes from the “bottom-up” perspective these voices can lend to historical context, which stands in contrast to the “top-down” approach taken by most common curricula in international schools. Rather than focusing on political figures or military leaders, oral histories enable citizens on the street to share different perspectives as “experts of their own experience.”

Harper explains the complexity of family histories can be captured through oral history projects, though teachers often explore this topic by asking students to draw their family trees. Many consider family tree assignments in biology and humanity classrooms—which assume all families have access to these genetic data—to be ostracizing for students whose families do not conform with typical genealogy.

Additionally, these assignments depend on students being able to trace their roots for several generations. Students from populations in which the memory of their ancestors was purposefully wiped out cannot participate, therefore these projects can prove traumatizing for young people.

Oral history has the advantage of working to make humanities more inclusive, and thereby also more relevant and relatable. Students have ownership of history and what they want to learn about the past.

Learning opportunities for students

Humanity educators cite the development of hard skills, things like questioning, historical orientation skills, and source analysis, as a benefit of collecting oral histories. But the benefit of this practice extends to teaching valuable lessons of humility and empathy.

“When students become oral history practitioners, they find themselves—perhaps for the first time—really listening to other people’s stories.” Harper extends this thought to explain the power behind this work and urges students to become more empathic through this process, helping them develop interpersonal and intergenerational relationships.

The loftier goal of these teaching practices strives to raise a generation of “upstanders” rather than bystanders. To guide a generation who will never again enable atrocities like the Holocaust and Apartheid to inflict pain for so many years.

For Harper the power of sharing stories has a profound impact beyond studying history. When Harper interviewed a former neo-Nazi for her work, she understood the importance of recording the experiences of victims, rescuers and even perpetrators. Eventually, she built a relationship with this individual and introduced him to Phillips, who shared her story with him.

A powerful moment for Harper was when Phillips greeted the two in German. “She swore herself to never speak German again. But on that day for this ex-neo-Nazi, she broke her oath and she spoke German,” Harper tells of this amazing story of reconciliation.

Start your own history

Those in international schools, or teachers thinking of joining the community of global educators, oral histories remain a source of untapped stories from students’ families. And a valuable reminder that their family history is worth telling.

“I want students to realise that we all have stories to share, that no one group of people is more important than another, and that—no matter the circumstances—people always have choices.”

For teachers interested in exploring the practice of oral history more, check out some of these resources:

- Oral history collection guide – British Library