I used to assess potential teachers for Teach First. We looked for evidence of resilience by asking interviewees to describe situations in which they had overcome challenges. Often, the most convincing were the ones who had this sort of experience ready-made, off-pat, flowing mellifluously off their tongues: ‘I completed the Duke of Edinburgh Gold Award’, ‘I spent six months in Korea teaching English’, ‘I worked on a project in Borneo rescuing orangutans’.

These were compelling answers, but provided by people who were privileged enough to afford them. The type of people who, to quote Pulp, could call their daddy and stop it all. Was hiring them really ‘addressing educational disadvantage’?

This is not to say that the less privileged candidates had not faced hardship and developed resilience – in fact, it is highly likely they had overcome far more authentic challenges than the other candidates ever would – but they couldn’t parcel up their experiences neatly with a ribbon and a label stating ‘Gap Year’ and present them confidently in an interview. It all made me feel a bit uncomfortable.

Nevertheless, we needed to know they wouldn’t drop out. Students need teachers who stick around, and the charity wouldn’t have been much use if they couldn’t promise schools that. So the questions had to be asked, and the evidence was necessary.

Perseverance is key

There’s no doubt that successful people are those who can demonstrate perseverance. It is one of the key skills employers look for, as argued by Yvonne Roberts in her highly readable paper: ‘Grit: The Skills for Success and How they Are Grown’ from 2009.

So, as educators, how can we give students a hard time when all we want to do is support them? How do we manufacture challenges?

There is a strong argument that an international school on a good day provides an authentic challenge to an expat student, who may need to adjust to an unknown country, immerse themselves in a brand new culture, often learn a different language, and assimilate themselves into a school that’s almost certainly like no other they’ve attended before.

The same can be said for international teachers. We take on a new role, in a new continent, often having never met any of the faculty in person. It’s an enormous leap of faith, and it provides us with a genuinely challenging set of circumstances. But we emerge the other side of it, sparkling, with a CV that kicks ass and a thousand gritty stories to tell.

International teaching in the midst of a pandemic

This year has been more challenging for international teachers than any other. We’ve been cut off from our homes, families, classrooms, students, relying only on the internet to maintain connections, both professional and personal. Nevertheless, there are many examples of teachers who have turned this challenge into an advantage; COVID has generated plenty of grit, and pearls have been formed.

Kate Roberts is a whole school counsellor in an K-12 international school in Vietnam. The country has taken a hard line in dealing with coronavirus, relying on the compliance of its people in the face of very strict laws, often decided the night before they come into force. Kate and her family, Colin, Head of Music at the same school, and their two kids Amaya (6) and Megan (4), were shut inside their two-bedroom apartment for four and a half months. They were not supposed to cross their own threshold. Their building’s guards became their captors.

Life had to go on

The girls needed to be educated, entertained, engaged with, and both parents were working full-time online. Kate’s job was to counsel a school of staff and students through managing their new realities: a huge responsibility for one person. The family had to find food to eat, they had to exercise, they had to stay sane.

But life went on in other ways too: one day Megan fell and smashed her front teeth. Kate smuggled her out of their building and tried to take her on her motorbike to a hospital, but at the end of each road they rode down she found a barricade of barbed wire that extended right across the pavement. She was forced to take her little bleeding girl to an off-duty dentist who lived in her building, who could do little more than recommend painkillers.

Sometimes it was hard to find food to eat: WhatsApp was full of messages from friends sharing inside info about where they could find a few eggs. The Army delivered food packages, often containing green slabs of what used to be pork.

And this was the privileged expat teaching community, continuing to receive a regular salary into their bank accounts each month. Huge numbers of local Vietnamese people were on the brink of starvation. Kate signed up to Zalo, an app that connects those in need with those who can help them. This shone a light on the reality of the crisis. Thousands of people needed help more than they did.

Finding joy in the little things

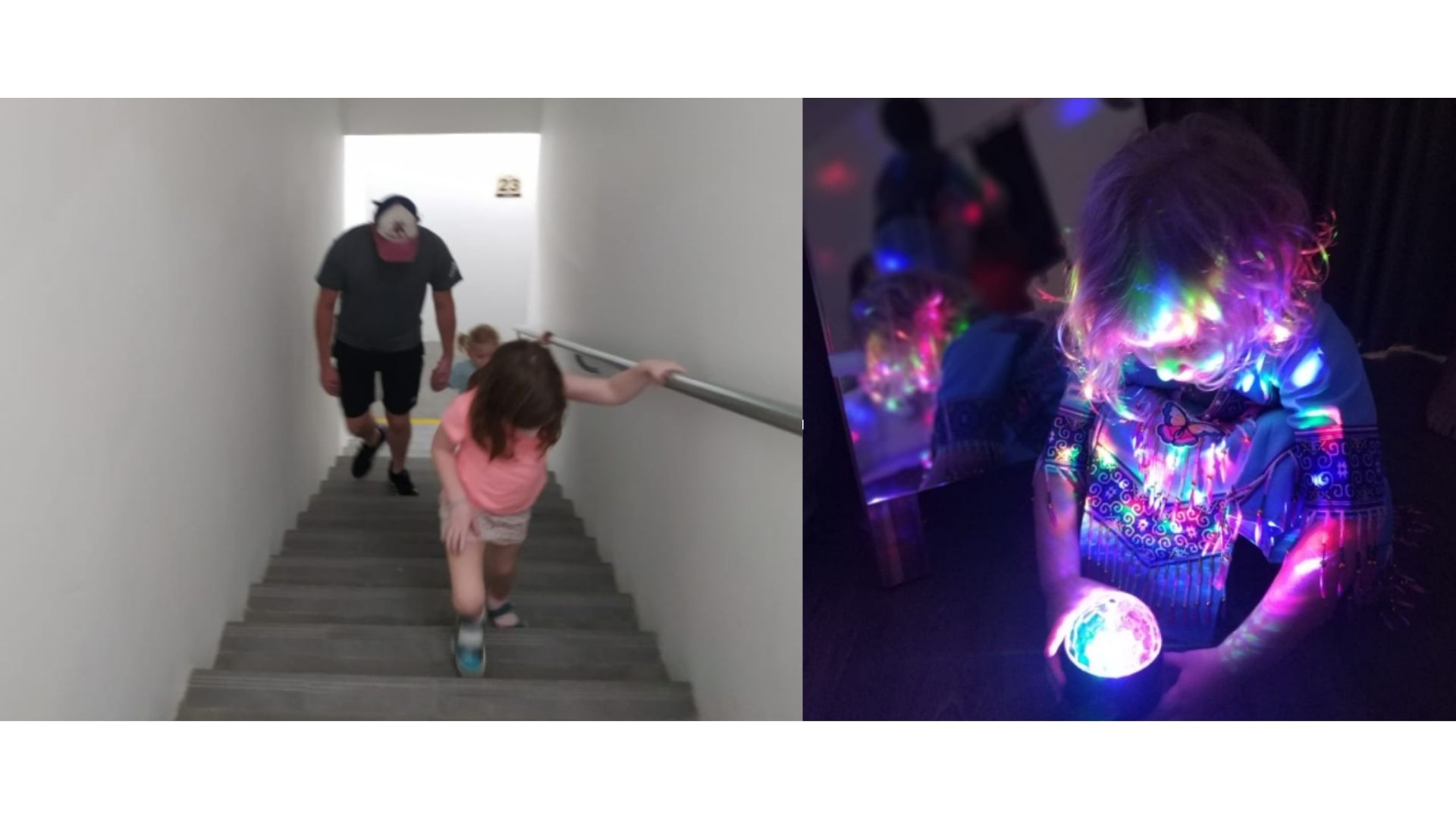

The family found freedom in unlikely places: the basement car park became the place where both girls learned to ride a bike; the roof became a dramatic venue for water fights; the balcony served as a sunlit bathroom.

But it was the stairwell that provided Kate with her own sanity. She decided to celebrate her birthday by raising money for the Saigon Children’s Charity, walking up and down the thirty-four storey building forty times: enough distance to replicate the journey to the top of Everest.

She trained for weeks with her daughters cheering her on, and this daily ritual became the outlet for all the frustrations of her situation. There was no natural light in the stairwell, no fresh air, and an average 31 degree heat, but she had no other option. By the end of the day of her climb she had spent 19 hours and 44 minutes sweating, but had raised enough money to feed 9000 people.

Help from the wider teaching community

The school community was also a great help to her, with regular check-ins online. The school did all it could to support their teachers, and this has had the surprising result of ensuring that the staff turnover for the end of this year is about the same as any other, a testament to the care they have shown to their faculty.

It proves to us that the success of an international school relies on the strength of its community. Teachers need a team around to help them through the tough times.

Kate wonders what impact this has all had on her kids, but also reflects that it has given them some incredibly special times together as a family. They danced in kitchen discos, performed science experiments together, and used their precious eggs to bake cakes.

The end of lockdown

When they were finally allowed out of their building at the end of lockdown, Kate took Amaya on a motorbike ride. The girl asked her mum about everything she saw, down to why the bridges they crossed had been built in that particular way. The onslaught of stimulation had triggered a torrent of questions. A mind had been jump-started again. Their journey to the supermarket turned into a wild adventure exploring the new.

There is no doubt that girls have been through a really tough time, but they have learned a great deal, and the model of grit and determination their mum has shown them will surely have a transformative impact.

My four-year-old son has taken to describing his mood as either a rainbow or a rainstorm. I applaud his ability to articulate his feelings so poetically. But as an adult who wants to squeeze every last drop out of life, and I think all teachers who live overseas fall into this category, I know that most useful moods scramble together sunshine with showers. After all, a rainbow only appears after the rain has passed.

So, as we end this year, let’s hope more colourful times are around the corner for our students and for our own families. But if they’re not, at least we’re all better equipped to weather the storm.

In 2022, Teacher Horizons will be strengthening its function as an online home for international teachers; somewhere else you can find that all-important sense of community. To that end, we would like to tell more of your stories. If you have one to share, please email me at editor@teacherhorizons.com.