Edapt is a new, independent, apolitical social enterprise in the UK that supports, protects, informs and develops the teaching profession. It aims to provide teachers with an alternative to teaching unions. Here, edapt director of policy, Emma Whitehead, considers whether a similar model could be useful in other countries around the world.

A couple of years ago, I attended a meeting at which the then newly appointed Secretary of State for Education was speaking to a group of teachers about what his priorities should be. At several points in this meeting, suggestions for reform made by teachers were met with the response from other teachers that ‘the unions would never allow it.’

This brought back to me frustrations from my own experiences of teaching when staffroom politics could be more stressful than the teenage quarrels among pupils and could put an end to conversations about potentially positive change. When pupils became aware of tensions between their teachers, and the union influence on this, I became concerned about the culture we were creating for them.

John Roberts started investigating an alternative to unions in 2010, as an offer for teachers who wanted a different way of conducting themselves – both with policy makers and in schools. After two years of development, including commissioning independent research from LKMCo exploring what teachers think of their unions, edapt launched in 2012, and I came on board as Director of Policy.

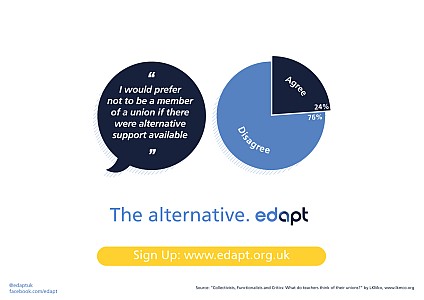

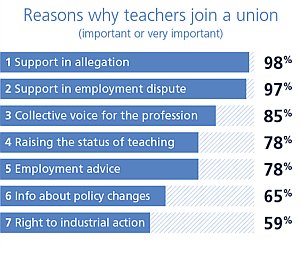

The research suggests that teachers join unions mainly for protection against allegations or employment disputes, and that 24% of teachers would prefer not to be in a union if there were alternative support available. edapt provides teachers with a choice as to where they get their support and protection, and ensures that it is professional, expert and impartial. My aim is to ensure that the experiences of our teachers can be fed into policy and that teachers can take part in policy debates as professionals.

There is a particular context to this need for edapt in this country, and the timeline of the development of the teaching profession, (on our Facebook page) shows that there is a long history of teachers trying to define their status. The fact that the most thriving remaining organizations for teachers are the unions suggests that historically, teachers’ identity as workers in need of a union has dominated over their identity as professionals. This creates a dynamic in which teachers are defined by their status as employees of the government, and the aims of education are increasingly defined by the employer. As a history teacher, I am particularly aware of the legacy of the trade union movement on our political context – and grateful for the employee rights and social change we all owe it. It is because of this history that it is a difficult but important line to tread to remain a-political, while still making the suggestion to teachers that if they don’t want to join a union, they don’t have to. It would be interesting to understand how the different histories of the profession around the world, and a different link between unionism, teaching and politics, has created a different dynamic.

Teachers are of course employees, and they should feel confident that their right to collectively bargain is respected, but perhaps in order for them to take ownership of the profession, this needs to stop being their defining feature. I consider myself to be a teacher even though I am not currently employed by a school – in the same way that a doctor may consider themselves a doctor, regardless of whether they are currently treating patients as an employee. I hope that edapt will allow teachers to feel confident enough that their existing rights as employees are protected, that they are free to establish a positive professional identity that can work constructively with policy makers and other professions.

It is important that creating this choice isn’t perceived as a political act in itself, but is understood as it is intended – to be offering a choice, in order to improve the working lives of teachers and ultimately the quality of education our young people receive. Having been a teacher and having now worked in a number of other organisations, I am aware of the mismatch between the level of support needed, and the level available to teachers. To take just one example of working time: in most jobs, you’re either working or you’re not, but in teaching, you can be teaching, using ‘PPA time’ (planning, preparation and assessment time), ‘directed time’ for parents evenings, or marking from home. Yet while in most jobs, employees know who to ask if they have a question about their contract, many teachers have no idea who supplies their HR services, or have never met their legal employer – which in the UK may be the governors, the local authority or an academy trust. Teachers need impartial and expert advice, and yet most pay for access to union volunteers who have an interest in using individual cases for collective bargaining. It would be interesting to hear how this differs in different countries.

A number of teachers we’ve met have said that the edapt model could be replicated internationally – particularly in the US, where this map shows the strength of teaching unions. Teachers who have experience of working in other countries and international schools could have a useful perspective on the extent to which the current unions in this country are representative of the teaching profession. They may have different insights into whether teachers should have a choice as to whether to join a union, and how this choice can be offered without being seen to undermine the positive intentions of unions to promote employee rights. Should teachers feel they need to be protected at all? Are there other countries that could benefit from an organisation like edapt?

If you’d like to find out more about adapt, please visit www.edapt.org.uk