A diverse and international classroom

In this classroom, there are several nationalities and even more languages spoken. Most of these students have lived in at least two countries, and their parents are doctors, engineers, teachers, civil servants and lawyers. In the next five years, they plan to go to university, train as professionals and start their own businesses. This is a diverse and international classroom that is building agile learners and changers for the future.

But this is not an expensive fee-paying international school. This is Amala. They run the first secondary-level program and qualification designed with and for refugee youth, offering displaced young people the vital chance to complete their secondary education. What this Amala classroom shows is that their world is not so far flung from international schools.

Redefining international education

How do you define an international education? This is a challenging question to address. The proliferation of international education by over fifty per cent since 2013 has made the task even more complex. The concept of ‘international’ can be elusive as it encompasses the movement of individuals across diverse national and linguistic boundaries, pushing against the constraints imposed by geography and politics.

When contemplating international education, our thoughts often gravitate towards a select group of privileged students and educators. This economic advantage often characterises them as an elite subset. It is crucial to clarify that acknowledging privilege is not an act of accusation but rather a form of descriptive analysis. For the students typically associated with ‘international education,’ this privilege signifies exclusive economic status, affording them access to abundant opportunities and resources beyond the reach of the majority of global youth. This privilege, however, does not diminish nor simplify the challenges these students face regarding their identity, sense of belonging, and internalized biases.

Danau Tanu aptly points out that while international educators educate millions worldwide and claim to foster ‘global citizenship,’ they often exhibit a Western-centric bias. Despite its close association with privilege, international education fundamentally aims to envision the world as a shared social sphere, where individuals from diverse backgrounds, traditions, contexts, and levels of privilege come together to acknowledge their shared humanity and collective responsibilities towards the future. It serves as a pathway to foster peace through education.

Amala’s mission: empowering refugee youth through education

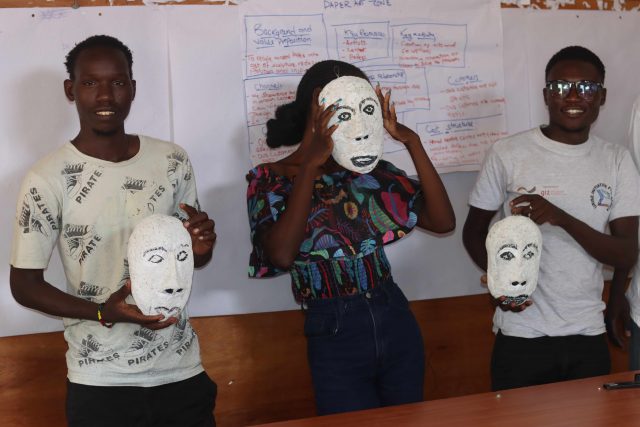

The power of education is what UK-based charity Amala is on a mission to harness, to transform the lives of refugees, their communities, and the world. Amala is a pioneer in post-primary education for refugee youth and offers the first upper secondary program designed with and for refugee youth, the Amala Global Secondary Diploma. The education charity also runs Changemaker Courses through which learners develop agency and become more aware of our shared social sphere through informal courses such as Peacebuilding and Ethical Leadership.

Amala was founded by two United World College (UWC) alumnae, Mia Eskelund and Polly Akhurst, who, having experienced the power of a prestigious international education themselves, decided to apply a similarly transformative approach to education for youth in refugee contexts. The Amala curriculum was developed in collaboration with one of the largest international schools in the world with expertise in values-based curriculum development, UWC South East Asia, as well as refugee youth and 150 educators. Amala programmes have to date reached over 4000 youth, with the aim of helping them turn their hopes for their futures into reality and supporting them to become changemakers on a local and global scale.

Amala students share many things in common with what one might think of as a typical “international school student”: multilingual, adaptable to new cultures and customs, and studying alongside those from dozens of other nationalities. They have a strong desire to make positive changes in their communities and the world. Amala students, however, are mostly refugees, from crisis-affected backgrounds, who have not previously had the opportunity to complete their secondary education. Fifty-nine per cent of refugee youth do not have the chance to go to, let alone complete, secondary school – a staggering figure which is even higher in low and middle-income countries.

Global education crisis and the future of international education

Education systems globally are falling short of providing the skills young people need to thrive in an ever-changing and challenging world. To work towards ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes (Sustainable Development Goal 4), international organisations including UNESCO and the OECD are advocating for systemic changes to traditional educational models. An education for the 21st century, one which equips learners with the skills to solve the world’s most pressing challenges, is a vision shared by Amala and international schools.

Intercultural learning is deeply embedded in the Amala teaching approach, and Amala’s dedicated educators, who are recruited from the local communities in which they work, draw on a diverse range of cultural contexts to provide meaningful and purposeful experiences for learners. Instead of exams, Amala takes a competency-based approach to assessment, marking a bold move away from traditional education systems, in its focus on evaluating students based on their ability to apply their learning to real-world challenges.

The Council of International Schools (CIS) and New England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC), agencies which usually accredit international schools, granted accreditation to Amala in early 2024, making Amala the first organisation working in a refugee context to have its education benchmarked with international standards and practices. Accreditors were stunned to see a world-class, global citizenship education taking place in low-resource, crisis-affected environments. There is a strong intersection with the missions of international schools and Amala, which both recognize the power of education to create a better future not only for their own students, but for the world at large. With this in mind, Amala is currently creating an international schools network to nurture the next generation of global citizens, bringing schools across the world together into a community which will commit to enabling students to become passionate advocates for equitable education.

Reimagining global citizenship through education

So what is international education? It extends beyond privilege and circumstance. It is education for peace and a better world, where we acknowledge differences and challenges without judgement. It is about developing global awareness, adaptability and the drive to create positive change – qualities that Amala shows are just as relevant for refugee youth as for students in fee-paying international schools.

The world needs the talents and potential of all young people to solve the big challenges of our times, and by broadening the concept of international education, we can support a more inclusive approach to what it means to be a global citizen. The true power of international education is in its ability to bridge differences, promote understanding, and nurture the ability and willingness of students to create the change they wish to see in the world.

Thank you Sophie (International Adviser at Teacher Horizons) and Cloe at Amala Education for this inspiring blog post.